By Jay Mitra, Professor of Business Enterprise and Innovation, Essex Business School, University of Essex, and INSME Board Member.

This Issues Paper has been developed for the 2022 INSME Annual Meeting “Empowering SMEs: economic diversification and green growth” held in Baku, Azerbaijan. Learn more on the event here.

1. Introduction

This Issues Paper provides an outline of some of the questions about climate change and carbon emissions and their specific implications for SMEs. The objective is to stimulate discussion on the issues raised in the paper. The paper has been prepared for the 2022 INSME Summit being held in Azerbaijan on 1 and 2 December 2022.

2. Background: Environmental Crisis and Its Impact

The Paris Agreement adopted by 197 nations at COP21 in 2015 limits the global average temperatures to well below 2°C and pursues efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C. above pre-industrial levels. Holding the warming to 1.5°C will save eleven million people from exposure to extreme heat, sixty-one million people from drought. Around ten million people will be saved from the devastating impact of rising sea levels. The setting of Net Zero targets by governments followed by a strict regime of implementation of public policy by business and industry are understood to be central to any form of adherence to the target of 1.5°C. Deep cuts to emissions in line with 1.5°C pathways and the permanent removal of any remaining greenhouse gases will be needed in order to achieve these targets – both of which are critical to addressing climate change. (Carbon Trust, 2022). This then is the baseline for actions pertaining to controlling the adverse effects of global warming. What then does this mean for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs)?

3. SMEs and their Green Economy

The Big World of Small and Medium Sized Firms

We have a classic policy conundrum. The Net Zero Carbon focuses on the Fortune 500 size companies, but in 2021 there were an estimated population of approximately 332.99 million SMEs worldwide, which is a shade more (around 1%) than in 2019 when there were 328.5 million, and a considerable jump (over 60%) from the beginning of the century when the figure was 204.2million. They represent more than 90% of all business around the world. SMEs account for 99.9% of all businesses in most countries. Crucially, an International Labour Organisation (ILO) study reveals that seven in ten workers are self-employed or in small businesses. Data obtained by the ILO from ninety-nine countries found that these economic units account for 70 per cent of total employment. These findings have significant implications for employment, enterprise support policies in general and adaptation to climate change world-wide. Size matters but not in the way that we reflect on the point when we discuss the role of businesses. The quantum of SMEs is far larger than large firms. So is the effect they have on jobs. The policy agenda appears to show interest in the size of larger firms but is less cognisant about the larger overall size of their smaller counterparts.

The Carbon Footprint of SMEs

If we take the example of the United Kingdom (UK), one of the leading players in advocating climate change policies, only 9% of small businesses, and 5% microbusinesses measure their carbon footprint according to a survey of the British Chamber of Commerce. Smaller firms tend to have limited access to capital and fewer resources, which implies that decarbonising can be an overwhelming target for achievement by 2050. The UK government amended the Climate Change Act in 2019 by introducing a target of at least 100% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. The 6th Carbon budget in 2021 aimed to set a target of reducing

emissions by 78% by 2035 and businesses with more than 250 employees are legally required to report their emissions under the Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting policy. Given the increasing urgency to combat climate change there are inevitable worries over the speed with which policy changes are taking place and the readiness of the 6 million UK SMEs employing seventeen million people to report the emissions. (Vella, 2021) There are six million small and medium sized enterprises in UK, employing 16.8 million people. The outcome of this tension is inadequate levels of scrutiny of greenhouse gas emission and lags in the implementation of tailored policy, support structures and adoption of appropriate action by SMEs.

If smart policies and support mechanisms are to be introduced to support SMEs, then obtaining an overview of the nature of the environmental crises and the specific question of carbon footprints.

Measuring Carbon Footprints

Carbon footprints are measured in categories or types called “scopes,” which are defined by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which is an internationally recognised standard for reporting emissions. (BCC, 2021) The framework is:

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from facilities or equipment the business owns or controls. These include everything from burning gas to generate heat for manufacturing processes to fuel burned by company vehicles. Reducing scope one emissions will require replacing equipment or change of procedures and processes

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions from energy bought from suppliers. This refers principally to electricity which is generated off-site but used on-site. Switching to a supplier that only buys renewable energy is an uncomplicated way to decarbonise, but care beware of greenwashing, which may mean some care is needed to verify the green credentials of a supplier.

- Scope 3: Indirect Emissions from company supply chain. These emissions are linked to the activities of your business, including business travel, purchased goods and services, water and waste. These are not directly generated by the business or the energy they buy. They are known as value chain emissions. For most businesses, scope three emissions make up most of what we know as carbon footprint. Measuring scope three emissions can be complex.

Scope 1, 2 and 3 reporting is drawn from the Greenhouse gases (GHG) protocol and was created by the world business council for sustainable development for companies to understand reporting categories. While each scope offers different opportunities to cut emissions, Scope 3 emissions are the hardest to eliminate and the biggest obstacle to reaching the net zero goal. Setting realistic targets by working out what reductions will be required each year to reach net zero by 2050. Interim targets allow to monitor the progress and make corrections accordingly.

While these ‘scopes’ are overarching issues covering all types of businesses, the assumption behind these issues appears to be framed by the notion that all businesses can be covered by these scopes. Not all businesses are the same and not just because of their size.

Managing energy could be a neat and straightforward way of making breakthroughs in generating a change of approach to carbon emissions by SMEs

Energy Management

Energy Efficiency is the quickest and cheapest way to cut the emissions. Scope 1 and 2 can be immediately tracked and cut by considering building efficiency from building fabric measures to reducing heat and cooling loss or even servicing and replacing boilers. (BCC, 2021)

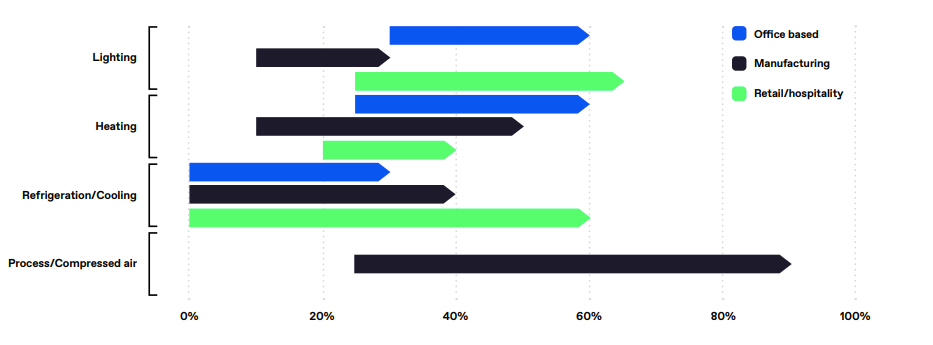

The Figure below shows the range of energy use system by system (as in plant processes, refrigeration and cooling systems, heating and lighting) typically seen by SMEs to be of importance. The pattern varies significantly by business sector.

The uses of energy are a function of the sector in which SMEs are located. Consequently, nuanced approaches are necessary to arrange for energy saving strategies. Table 1 below shows the end uses of energy that dominates in a particular sector, highlighting the areas with most energy saving potentials (Carbon Trust, 2022)

Table 1: The Energy Saving Potential of SMEs in Specific Business Sectors

| Business Sector | Systems with energy saving potential |

| Food manufacturing | Lighting, refrigeration, motor-driven processes, and space heating |

| Office based | Lighting, heating, and IT systems |

| Retail | Lighting, heating, and refrigeration |

| Hospitality | Lighting, heating, and catering equipment |

| Construction | Compressed air, mobile plant |

4. SMEs and their Concerns to Net Zero Targets

Many small businesses have already started their net zero journey and they can be seen as catalysts for transition. However, there are various challenges being faced by SMEs across specific sectors and geographies, and there are some common obstacles confronting them. SMEs in some cases do not have the in-house sustainability expertise, time, or resources to tackle their carbon footprint, and may find it difficult to measure and reduce value-chain emissions.

In addition, it is important to consider the key drivers of emissions reduction on SMEs, which include legislation and government regulations, high operational costs, demand by customer, competitive pressures and general concern about the environment.

5. What can SMEs Do?

SMEs need to focus on implementing the most straight forward carbon reduction opportunities before tackling longer term more complex initiatives. The key drivers for starting a journey to net zero include: (Carbon Trust, 2022

- Cutting costs and increasing profits

Costs can be reduced through measures such as introducing energy management practices, installing smart meters, energy-efficient lighting and heating systems, re-designing products that require fewer inputs without sacrificing utility, reducing volume of packaging, and switching to local suppliers to decrease logistics distance by switching to recycled materials and the reusing of waste productsLarger companies expecting their suppliers to act.

- Larger companies expecting their suppliers to act

SMEs need to engage in this process to avoid missing future contracts and growth opportunities, as the wider supply chain increasingly demand low carbon products and services being able to respond to the demand will give a competitive advantage to the organisation.

- Customer expectation

Customers expect companies to make ethical decisions on their behalf and going green can attract new businesses and customers’ base

- Opening new markets

Offering innovative ‘green’ products, services or business models may open low carbon business opportunities

- Enhancing reputation

Cutting carbon emissions and helping to combat climate change demonstrates a degree of corporate social responsibility.

Strategically a future roadmap for SMEs could follow with SMEs making a commitment to reach net zero by starting with clear plans for calculating their baseline emissions. The most vital in the transition for SMEs to a low carbon future is to know their emissions at first and then the amount which they need to cut. They could then switch to a green tariff and arrange for that switch to correspond to government policies which will increasingly be focused on greener and sustainable activities. Soon taxation and other allied activities will be driven according to net zero policies by governments. An actionable plan to reduce and achieve the NZE will enable SMEs to remain operational in the future.

6. How can government policy support SMEs?

Government plans for SME decarbonisation to enable more joined-up, cross-departmental policy making is vital if small businesses are to overcome the common net zero challenges that they face. Time, knowledge and money are probably the biggest constraints in particular upfront financing and time and relevant knowledge acquisition and application. Activities with a national framework but which can be coordinated and implemented at regional levels might stand a better chance of success than overriding national ones (EST 2022). These include inter-alia:

A clear regulatory timetable is critical to any plan that supports SMEs. SMEs tend to respond to emerging regulation so that they can arrange for any investment planning in line with the known policy development and implementation timelines. The earlier governments establish clear and firm dates for future low carbon standards, the better the chances of SMEs being enabled to reduce their decarbonisation costs and risks.

Joined-up support framework. This should couple ongoing awareness raising with a single contact point for SMEs. The contact point should provide access to financing support, information on regulations, foot printing and audit services, as well as peer learning networks.

Targeting the Smaller Business. In May 2021, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) in the UK launched a new campaign called ‘Together for Our Planet’, urging small businesses to cut their GHG emissions in half by 2030 and to achieve net zero by 2050, starting with small practical steps. The government published the conversion factors allowing to calculate the carbon dioxide equivalent of different gases.

The proposed steps to achieve net zero by 2050 are as follows:

- Calculate the Company carbon footprint. To lower the emissions the first step is to calculate current emissions. Knowing the level and rate of emissions first is necessary before tackling them.

- Create a strategy and stick to it. Once operational emissions have been calculated, the next step is to create a strategy outlining how to work towards lowering and eventually eliminating the emissions. Setting an emissions baseline helps to provide a point against which changes in the number of emissions produced by a project in a reporting period can be measured.

- Bring staff along for the journey. Informing and educating employees about the ambitions for reduced emissions helps to improve the journey and should make the transition smoother. Equally, employees need to work on personal and professional approaches towards achieving the goals.

- Offset stubborn emissions. This includes sequestration of carbon – such as tree planting.

- Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Applications. In the transition and wake of NZE, the hydrogen application in particular the fuel cells in power and transport can help achieve the targets by huge levels.

These recommendations do not necessarily constitute policy but they function as levers for working with SMEs.

Governments across Europe have set up various projects including those under the auspices of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and while these are well-intentioned, they tend to face specific challenges including:

- Short project timeframes – typically 3-4 years for the delivery of a support programme, are likely to have only a limited impact given the many barriers to SME decarbonisation, especially when some project partners have limited experience.

- Lack of learning between projects -the exchange of inter-project knowledge with exclusive methodologies can be limited and evaluations are ad-hoc, informal and not shared in the public domain. Information resources can be reinvented many times across multiple projects instead of being shared because of poor communication.

- Geographic variation and ‘patchwork’ support framework: Too many regional projects providing irregular free audits and funding support for low carbon measures results in businesses not knowing whether they would qualify for support, or not.

- Possible ‘crowding-out’ of private activity: Unplanned and unexpected announcement of considerable subsidised financing opportunities or the provision of free energy audits, can have an adverse crowding out effect on consultancy/auditing/foot printing services or private financing offers in that area.

Source: EST (2022)

7. Examples of International Best Practice

Based on work by the conducted by the Energy Saving Trust (EST) for the European Leap4SME project some good practice examples were identified.

Companies in Malta and Poland are offered subsidies to buy energy auditing services from auditors who are trained to a national qualification. These are supplemented by successful awareness campaigns to encourage the use of the auditing programme. Delivered by the national energy agency in both countries the campaign involved extensive communications through the media. In Poland additional regional events are organised to this end, and the energy professionals engaged in the programme have undertaken almost 60,000 consultations in Poland since the scheme’s launch in 2017.

The Austrian AWS Investment Bonus programme is a good example of a successful incentive scheme, providing non-repayable grants to support businesses to invest in in environmentally friendly technologies (among other priority areas) subsidised at double the standard rate. These include investments in green technologies, digitization, health, and life science which attract a subsidy of up to 14% of acquisition costs. The scheme is open to all business types and sizes. Since its launch on 1st September 2020 until the end of December 2020, 67,800 applications were received of which 93% (or 63,054) of which came from SMEs.

In Portugal, a new funding programme from the government agency responsible for SME competitiveness set up in 2022, supports industrial companies of any size to: adopt low carbon processes and technologies; adopt energy efficiency in industry; and incorporate renewable energy and energy storage. There is €705 million funding, of which €200 million must be allocated to SMEs.

Ironically, and despite its promotion of the cause to curtail carbon emission, there is no funding support for SME process energy efficiency, beyond innovation competitions.

Various EU countries have implemented peer networks for SMEs, aimed at energy efficiency opportunities and eco-innovation. The ‘Learning Energy Efficiency Networks’ in Germany supports 10-15 regional businesses in specific sectors (e.g., food, healthcare, metal products), with an external facilitating agency such as the state innovation agency, the Fraunhofer Institute, engaged in enabling its roll out. In these networks members expert advice, access to audits and share experiences of, and best practice. They work together to set targets for energy reduction over a period of typically 3-4 years. However, membership of these networks is not restricted to SME exclusive, and there is an additional bar in Germany where the average threshold for membership is energy expenditure of at least €0.5 million per year, and with members’ contributions ranging from €6000-8000 pa. Early evaluations have identified substantial benefits, such as financial savings, for members. Typically, an average of 30% internal rate of return (IRR) have been achieved across thirty pilot networks in the last decade.

Finally, a word or two about technology, and especially digital technology, its development and its innovative uses in the context of climate change. Could it have an effect on the behaviour and actions of SMEs and in shaping government policy to assist SMEs in negotiating the realities of Climate change?

8. Technology and Innovation

It is believed that the rapid evolution of digital and other technologies should help all businesses and the wider economy to meet some of the challenges posed by the climate crisis The primary purpose of digital technologies is to enable SMEs to use their information and those in their networks, to be harnessed “as dynamic assets for driving a transformation agenda.” Table 2 below provides some examples of how digital technology can contribute to systemic and operational change to support businesses including SMEs.

Table 2: Digital Technologies for Climate Change

| Augmented Reality | Edge Computing | The Internet of Things |

| Augmented reality (AR), for example, can view the real-time effect of climate change, such as flooding or heatwaves, and project what could happen without action. The environmental charity Earth Watch, Europe have used AR to build a virtual city to create a new architecture based on simulated nature-based solutions to plan for and manage actual disasters. | Edge computing helps to store data at what is referred to as the ‘edge’ of an infrastructure network so that it can stop large volumes of information from being sent over the global network. It does so by running fewer processes in the cloud and shifting the data to local environments, such as an individual user’s computer, and reducing energy requirements. The alternative would be almost unquantifiable use of electricity by all the traffic, storage, and data processes. By reducing bandwidth consumption, it can eventually save energy and the planet. | The Internet of Things (IoT) represents an extensive network connecting objects or ‘things,’ including wearable health monitors, sensors in the refrigerator, communicating satellite navigation systems in cars, and many more. Since 2020, there have been over twenty-six billion connected devices. What IoT does is to play a key role by collecting data from sensors and connected products and devices, which can be used to reduce the human footprint, waste, and CO2 emissions. According to Ericsson, the use of IoT has the potential to reduce emissions by as much as 63.5 gigatons by 2030 and all industrial sectors should participate |

While large firms dominate the technology scene SMEs, and especially new technologically niche firms have emerged as important players in the delivery of solutions to climate change problems, using digital technologies as instruments of intervention. A start-up firm, for example has developed a platform that maps existing technical and scientific capabilities to reach the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) using keywords and other variables. Users apply these keywords to search for knowledge about a specific topic and look for connections with different applications or synergies in their area of interest, and the materials they use. Yet another new firm uses AI and an IoT system to report on waste types and amounts to reduce and improve on inefficiencies in waste collection. A third firm builds greenhouses on the rooftops of commercial buildings using excess energy and waste as inputs. They provide fish and vegetables for usage or product in supermarkets and other commercial buildings. A fourth example is that of a mobile and web application that provides recyclable information on products and packaging to end-users with an integrated reward system (Mitra, 2021).

The work of disparate, individual SMEs can be leveraged and enhanced through clear, business development strategies that are shaped by innovation. The message is simple. Intractable problems such as climate change and carbon emissions can only be dealt with a reversal of economic thinking and activities and a proactive approach to innovation. That innovation using technology to both improve productivity and change the direction of growth, development and human wellbeing is clearly understood in policy circles is not denied. And it is smart SMEs which are often the driver of bold initiatives which larger firms find hard to negotiate because of entrenched financial and organisational arrangements.

Instead of relying on traditional and stylised models for economic and social change that are simply handed down from government to industry and then consumers as part of a traditional linear value chain, new thinking on, for example the benefits of a circular economy buttressed by digitisation could help. This requires new real-time infrastructure development to meet real-time challenges centred on networked based models of policy and practice operational at local/regional levels through the adoption of community compacts for ideas generation, validation, decision making and evaluation. Digital technologies make that possible. How can this be accomplished?

The transformation agenda offering prospects of innovation based on ideas of the circular economy is dependent on five key conditions – technology, the marketplace, skills and knowledge, policy and community embedding (Mitra, 2021).

Noting that all firms operate within institutional, regulatory, and political frameworks, a circular model might help to increase capital flows and better public appreciation as evinced, for example, in the EU’s promotion of looping of materials through waste regulations, and in the use of supply chains, a policy which reflects the agenda of the circular economy. Digital technology advantages are being built into a number of start-ups’ operations, including the adoption of existing web-based platforms for the sale of products and services. By enabling firms to focus on existing solutions, firms can concentrate on business development. A supplementary consideration is the use of big data through agencies working with SMEs to support collection, retrieval, interpretation and use of data.

The effective functioning of the marketplace for digitization and the circular economy is dependent on market behaviour and the offer of key incentives. While consumers need to be weaned off excess consumption and incentivised to accrue the benefits of, for example, recycling, firms can be encouraged to question the value of the technologies and an abundance of innovation for which the market may not be ready, and which might be hostile to the environment. Market behaviour is inevitably governed by prices, the quality and convenience of products which need subsidizing especially in the early years of new green firms, and arrangements for governance which are innovative in scope as in more networked structures which include the communities in which firms are located.

9. Concluding Observations

For SMEs to play a more pronounced and productive role in the climate change management process a considerable amount of careful planning and work needs to take place. Both the role of SMEs and their federations and nuanced policy development by government are critical to enabling change. The platform on which this could be done best is innovation. Innovation does not always translate into something radically new. If policy incentivised SMEs to change behaviour in the routine aspects of organisational processes, then that form of incremental innovation can be less burdensome for the average SME. On the other hand, the niche technology players need to be incentivised to harness the advantages of digitisation and related new technologies. Cultivating networks of climate innovation which are located in specific regions and thereby enabling appropriate contextualisation can overcome the use of generic policies which offer grand gestures but little by way of advancement of good practice.

References

Carbon Trust (2022) ‘The Journey to Net zero for SMEs’, online at: https://ctprodstorageaccountp.blob.core.windows.net/prod-drupal-files/documents/resource/public/The%20journey%20to%20Net%20Zero%20for%20SMEs%20guide.pdf Accessed on 11 Nov 2022

Vella, H. (2021) ‘How can Small Businesses achieve Net Zero Emissions’, Sage. Online at: https://www.sage.com/en-gb/blog/small-businesses-net-zero-emissions/ Accessed on 11 Nov 2022

British Chamber of Commerce BCC (2021) ‘Net Zero and SMEs: How can you act now’. Online at: https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2021/09/net-zero-and-smes-how-you-can-act-now Accessed on 11 Nov 2022

Enterprise Research Centre ERC (2021) ‘How can SMEs contribute to Net Zero’. Online at: https://www.enterpriseresearch.ac.uk/how-can-smes-contribute-to-net-zero/ Accessed on 11 Nov 2022

International Renewable Energy Agency IRENA (2020) ‘Planning with Net Zero Scenarios: Moving from Political Ambition to Country Level Pathways’. Online at: https://www.irena.org/events/2020/Dec/Net-zero-emission-scenarios-for-climate-policy Accessed on 11 Nov 2022

Anderson, M. (2021) ‘Global Environmental Crisis: What is it, causes, consequences and solutions’, AgroCorm. Online at: https://agrocorrn.com/global-environmental-crisis-that-is-causes-consequences-and-solutions/ Accessed on 11 Nov 2022

Kauffman, C. (2022) ‘From One Crisis to Another: What price for SMEs’, COGITO. Online at: https://oecdcogito.blog/2022/06/27/from-one-crisis-to-another-the-price-for-smes/ Accessed on 11 Nov 2022

Statista (2022). Estimated number of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) worldwide from 2000 to 2021. Available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/1261592/global-smes/ (last accessed on 18 November 2022)

ILO (2019) t, Small matters: Global evidence on the contribution to employment by the self-employed, micro-enterprises and SMEs. Available from https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_723282/lang–en/index.htm (last accessed on 18 November 2022).

EST (2022) How can policy better support SMEs in the pathway to Net Zero? Energy Saving Trust, UK. (last accessed on 15 November 2022)

Mitra, J. (2021) ‘SMEs, Climate Change and Digital Technology’ prepared by Jay Mitra for the 2021 INSME Annual Summit in Sofia, Bulgaria, ‘SMEs as Drivers of Sustainable Recovery’.